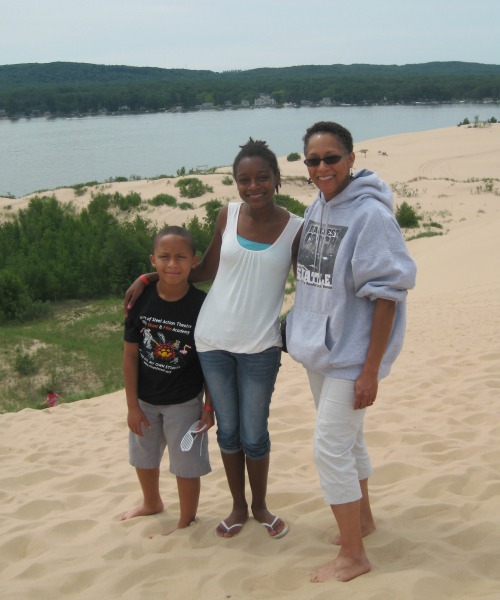

I am a middle-aged African-American woman, single mother of two, raised as the youngest of eight children by a mother with a 10th-grade education. I grew up on the East Coast in an impoverished and crime-ridden former industrial town where the illegal drug trade is now the mainstay of the economy.

I am a middle-aged African-American woman, single mother of two, raised as the youngest of eight children by a mother with a 10th-grade education. I grew up on the East Coast in an impoverished and crime-ridden former industrial town where the illegal drug trade is now the mainstay of the economy.

From the description of me above, some might have me currently pegged as uneducated, low class, struggling to make ends meet, and perpetuating the cycle of poverty I was raised in. The image of “welfare queen” might even come to mind, as my intersecting social identities (i.e., gender, race, class, and marital status) are characteristics of the so-called figure injected into policy discussions under President Reagan—an image that is socially constructed and influences news media stories and policy discussions today.

What’s missing from my social identity descriptors above are what Ahir Gopaldas (2103) documents as critical aspects of intersectionality: In my case, that includes:

- Not only what I have shared about myself, but what has been overlooked and not divulged;

- My story, in my own voice of how these interconnected social identities enable me to resist against daily oppressions I endure throughout my life; and

- What I plan to do to achieve social change, not only for my own life, but for others who also experience similar oppression.

If I were to share my story, I would divulge the multiple oppressions I continue to experience based on my interconnected social identities as a Black woman, single mother from a poor working-class family, in spite of achieving a PhD and being educated at the most elite institutions in the U.S. For example, as a single African American woman, I don’t get invited to many social events where important networking takes place for fundraising and advancing the mission of the Women’s Center I direct. However, I would also share the transformative experiences in my life that have served as catalysts for propelling me out of the cycle of poverty, such as having mentors to whom I turn when times get tough and difficult decisions need to be made and hearing reassuring words from others that I can keep moving forward when I make mistakes and disastrous decisions. Everyone needs this type of encouragement to succeed no matter what social identities you claim or oppression you experience.

If I were to share my story, I would divulge the multiple oppressions I continue to experience based on my interconnected social identities as a Black woman, single mother from a poor working-class family, in spite of achieving a PhD and being educated at the most elite institutions in the U.S. For example, as a single African American woman, I don’t get invited to many social events where important networking takes place for fundraising and advancing the mission of the Women’s Center I direct. However, I would also share the transformative experiences in my life that have served as catalysts for propelling me out of the cycle of poverty, such as having mentors to whom I turn when times get tough and difficult decisions need to be made and hearing reassuring words from others that I can keep moving forward when I make mistakes and disastrous decisions. Everyone needs this type of encouragement to succeed no matter what social identities you claim or oppression you experience.

Through my current role as Director of the University of Michigan's Center for the Education of Women (CEW), I have the privilege of addressing the multiple oppressions of women living in Detroit and Flint, Michigan – many who are women of color, living in poverty, and single mothers. The focus of the project is to develop state policy recommendations for inadequate childcare, transportation, and other basic needs; access to job training and education; and workplace policies that provide sufficient flexibility for managing work and life demands.

With a grant from the Ford Foundation, and with University of Michigan faculty and Detroit and Flint area social service agencies, activists, and advocates as partners, we are collaborating to gather the stories and examine what we know and don’t yet know about these women and their lived experiences (Please see our Michigan Partners Project Page for more information). We are encouraging them to share their own stories through their own voices. And TOGETHER we are in the midst of developing a plan of action – with a focus on changing state policies to replace archaic ones, such as not allowing women receiving Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) to fulfill their 40 hours/week work requirements by participating in full-time postsecondary education or training program. This is a no-brainer, given that data show that through obtaining advanced skills and education, there is a greater likelihood for social change toward moving generations of women out of the cycle of poverty.

This intersectional approach to our work is essential as we strive to advance economic security and mobility, not just for women in general, but more specifically for women living in Detroit and Flint. These women share common experiences of simultaneously battling to overcome the overlapping and multiplicative oppression of classism, racism and sexism, in addition to numerous other oppressions based on other social identities that are apt to be revealed as their stories evolve. Through this intersectional approach, our goal is not only economic security and mobility for these women, but almost equally important, as pointed out by Gopaldas (2013), are their human needs of recognition, acceptance, and respect.

With this in mind, I ask:

What are your intersectional social identities? How might your experiences relate to the plight of others who experience oppression based on these identities? How might you help those less fortunate than you?

I look forward to your responses below*, and I'd love your input.

*Note: You will need to register for an Institutional Diversity Blog account in order to comment, but you can get started right away by clicking here, or visiting our FAQ page for more help. Also, check out this video on "Registering for an Account on The Institutional Diversity Blog".

Dear Dr. Thomas,

I really appreciate your care for women, and thank you for sharing stories. Your blog will definitely help other women on how they can connect to resources for their future achievements. Yes, they have special needs. And you are a bridge that connects women with women and resources.

I had to get married when I was 15 years old because of my family. They forced me to get married at very early age. 13 years later my husband died. And I am a mother of 3 children. I don’t have any educations, and any skill to find a job. I just go to house cleaning to make money for my children’ education. People shouldn’t judge people who get married at early age. Million girls under the age of 18 get married each year because of their families. And also early age marriage is legal in many countries. I think marriage before the age of 18 shouldn’t be allowed in everywhere. The most dramatic thing is girls tend to drop out of school shortly before or when they get married. I don’t know how to help these girls because it’s in all over the world. Education programs around the world should increase girls’ school attendance. Government should take actions to end early and forced marriage around the world, so that girls can stay in education.

I and others who experience the same situation need acceptance and recognition. There should be free courses to help us get education. Then we will be able to get skillful, and find a job.

Tkartal